Yoghurt with a taste similar to what we might find in a grocery shop was something I gave up on for a long time. I made only room temperature viili for years, thinking that a good Greek or Bulgarian style of yoghurt was beyond me. At some point I decided I preferred the taste of this style of yoghurt enough to find ways to make it work, and now I make yoghurts far tastier and healthier than anything I can find for sale. In this article you’ll find my recipe, along with extra tips to make really good yoghurt every time.

How to make yoghurt

Heat milk in a saucepan until it reaches 82ºC (180ºF) or higher, hold it at or above that temperature for half an hour, if possible, and then let it cool to around 40ºC (104ºF).

Pour into jars, then stir through around 5 tablespoons (75ml) of yoghurt for every quart (litre) of milk.

Keep your culturing yoghurt at 40ºC (104ºF) for the next 6 hours or more (I find that 12 to 18 hours is best).

How to keep yoghurt warm during culturing

A couple of ways to keep yoghurt warm are:

• fermenting it in an insulated food jar such as a thermos.

• surrounding a normal jar with hot water in an esky (cooler) or on the edge of a woodstove dying down for the night.

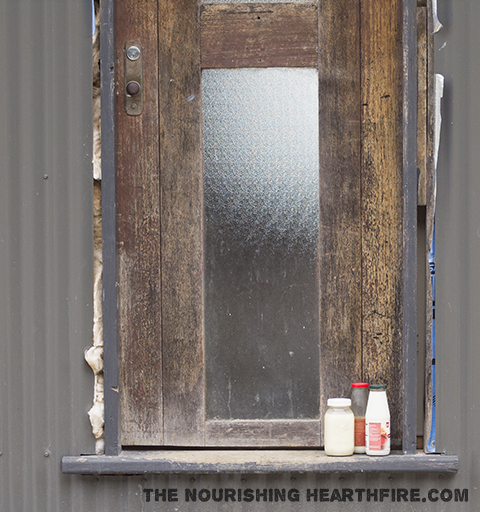

I use the latter method, as it means I don’t have to mess around with transferring yoghurt from one jar to another once it’s ready – I culture it in the same jar that I use for storage.

There are special non-electric insulated yoghurt fermenters available, where you fill it with hot water, place your jar of yoghurt inside, seal, and leave to culture, but I find the size of these limiting, as they will only hold a specific size of jar, and from my experience they aren’t that great at keeping the heat in.

There are also electrical gadgets, such as Instant pot and specialty yoghurt makers, but I avoid relying on electricity as much as possible so these are not things I have tried.

• In real life, the temperature does tend to drop over time, so it’s sometimes easier to start culturing it at a slightly higher temperature (up to 46ºC or 115ºF), and leave it culturing for twelve hours or more rather than six. Some of the helpful yoghurt bacteria will still be active in the lower temperatures, and the heat-loving bacteria will still have some time to grow during the earlier, warmer stages of culturing.

In winter I leave my yoghurt jar overnight in a pot of warm water on the edge of the woodstove as it cools down, and then refill the pot with hot tap water in the morning to give it more time to culture at high temperatures. I find that yoghurt tastes the best after around 18 hours of culturing in this way during winter.

Tips for making thick yoghurt

• Experiment with using milk from different animals or different sources. One of the goats here gives very creamy milk that makes excellent thick yoghurt, my other goats give milk that makes a thinner yoghurt. If I were mixing all the milk together I would not have noticed this. Full fat cows milk generally makes lovely thick yoghurt, and milk from a Jersey cow or other cow that gives extra creamy milk will make even thicker, lovelier yoghurt.

• Winter milk makes thicker yoghurt than summer milk. Sometimes it helps to just accept that winter is the time for thick yoghurt and in summer you might want to stain it through cheesecloth if you want it to be thicker.

• Yoghurt will be thicker if it is first heated above 82ºC (180ºF), and then left to cool to the culturing temperature. If you can heat it up slowly, or hold it at the goal temperature for half an hour, this will help to create thicker yoghurt. The high temperature changes the protein structures in the milk, to help create a thicker yoghurt.

• Allowing the milk to cool down and then reheating to 82ºC also can help make for thicker yoghurt.

• You can evaporate some of the liquid out of the milk, by leaving the pot on the heat with the lid off once it’s reached temperature – just observe the level of the milk you start off with, and then remove and allow the pot to cool once it’s reduced by ¼ to ½.

• For thick Greek yoghurt, allow your yoghurt to continue culturing at warm room temperature until the whey begins to separate. Pour it into cheesecloth and allow the curds to continue dripping whey until it’s as thick as you’d like it to be, anywhere between two and twelve hours.

Tips for reliable yoghurt culturing

• Yoghurt is best made at least once per week, to keep the culture fresh. It is worth keeping a small amount of yoghurt tucked away in the freezer, just in case your yoghurt gets contaminated or abandoned.

• Cultures that contain acidophilus seem to be more reliable home kitchen conditions

• If in doubt, add more yoghurt to start it off, rather than less. Some recipes advise using only two tablespoons for a litre (quart) of milk, but I always use 5 tablespoons and it doesn’t hurt it, it just makes the milk get colonised more quickly while the temperature is warm.

• To keep your yoghurt culture as active and pure as possible and avoid having to buy new culture, it’s a good idea to keep everything as sterile as possible: Heat and cool your milk in a pot with the lid on, heat-sterilise your jars, don’t leave them open to the air any longer than you have to, and be very careful with any jar of yoghurt that you’ll be using as a starter for your next batch – pour the yoghurt out rather than reaching in with a spoon (unless the spoon is heat sterilised). For even better results, make an extra smaller jar of yoghurt that you can use as your culture, and then it doesn’t matter what happens to your jar of eating yoghurt.